Karen Truelove, a Traditional Healer at the Dena’ina Wellness Center, leads a healing circle at Tyotkas Elder Center for boarding school survivors and others who were affected. From left are Tina Mulcahy, Mary Hunt, Tom Titus and Mary Lou Bottorff.

Healing circle provides space to address boarding school trauma

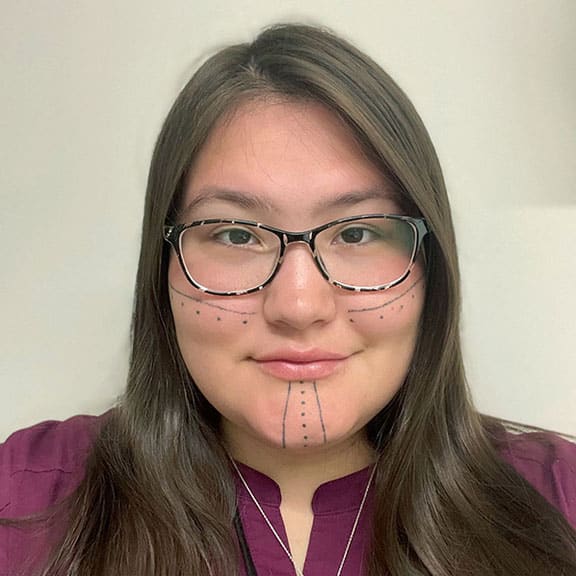

Last summer, a group of Elders approached the Tribe’s Traditional Healer about starting a healing circle at Tyotkas Elder Center for survivors of boarding school abuse.

While the initial focus for the Growing Through It, Healing the Generations healing circle was boarding school survivors, the policies and social attitudes of the boarding school era caused trauma for many people, whether an individual was forced to attend a boarding school or not.

Karen Trulove, the Traditional Healer at the Dena’ina Wellness Center, said many Elders were looking for ways to heal from traumatic events in their lives, and break the chains of generational trauma.

“I think that hearing people’s stories and sharing your own, you realize how connected we are,” said Tina Mulcahy, a participant in the healing circle. “In the Native community, we share our joy, and we share our pain. I really do think the path to peace and healing is that way.”

Participants in the healing circle have shared stories about being sent to boarding schools far away from their home, and how they were forbidden to express any part of their Alaska Native culture. They have talked about the abuse they suffered, and the effects that being disconnected from their family and community have had.

Some Elders who didn’t go to boarding school still remember being hit on the hands with a ruler or whipped with a belt in public schools, just for speaking their Native language.

Mary Hunt talks about her experience at a boarding school in Holy Cross. Behind her is a statue from the village gifted to her by Mary Lou Bottorff. They were in the facility at the same time.

Tom Titus said he didn’t know the term “generational trauma” – a term that describes how trauma can be passed down from one generation to the next – until he started participating in the healing circle.

“I used to fight. I wanted to get it out of me, and I didn’t know how. That’s what I feel like I’m doing here now. I’ve started understanding what generational trauma is. There’s a lot of emotions I’ve never let go of,” Titus said.

Mary Hunt said that she hopes that finding some healing for herself will also help her children.

“I find that healing takes place the more you verbalize your past. You can let some things go that affect who you are. If I’m changing, they will see it,” Hunt said.

Doris Lageson said the she is a firm believer in sharing.

“I believe that anything that’s happened in your past, if you hold those secrets in, those secrets come out in a negative way,” Lageson said.

Those negative effects can include health issues, as well as violence or substance abuse, Trulove said.

Last May, the U.S. Department of the Interior released the first part of an investigative report as part of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, an effort to address the legacy of federal boarding school policies.

From 1819 through the 1970s, the United States implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools throughout the country. The purpose of the schools was to culturally assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children by forcibly removing them from their families and communities. Attendees were discouraged or prevented from speaking their language or practicing their culture. While attending boarding schools, many children endured physical and emotional abuse and, in some cases, died.

Mary Lou Bottorff, right, leans in to hear as Tom Titus talks softly about how the boarding school experience affected his brother.

Benjamin Jacuk, a Kenaitze Indian Tribal Member, is a researcher at the Alaska Native Heritage Center and has become a subject matter expert on boarding schools in Alaska. Jacuk’s grandfather, Mack Dolchok, attended boarding schools.

Jacuk participated in a panel discussion on the subject at the Alaska Federation of Natives Convention last fall.

“It’s a really large history that has impacted not just me, not just the people on this panel, but every single person in this room,” Jacuk said.

The investigation found more than 400 federal boarding schools across 37 states or then territories, including 21 schools in Alaska.

Another panelist, Theresa Sheldon, Director of Policy and Advocacy at the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said that in addition to boarding schools, more than 170 facilities have been identified in Alaska that were not included in the definition of boarding schools, but served the same purpose.

Jacuk noted that about 40 percent of the federally recognized tribes in the country are in Alaska, making the state an important piece of the boarding school discussion.

“That means Alaska is ground zero for a lot of the structures of violence that we see that had taken place throughout the United States, then exported to Canada and the rest of the world,” Jacuk said.

Jim LaBelle Sr., a panelist and First Vice President for the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, said that the legacy of boarding schools remains.

“Echoes of boarding schools in Alaska are still with us today,” LaBelle said. “All we have to do is look at our national suicide rate that’s higher than any other ethnic group in America. All we have to do is look at the 40 percent Native incarceration rate in Alaska, when we only make up 15 percent of the population. We need to also look at the echoes that are still with us today relative to the 60 percent of children in foster care (who are Alaska Native). I really want to emphasize that these echoes are primarily the result of the many generations of people like yourselves and myself experiencing boarding school.”

Jacuk said that many Alaska Native people, and Indigenous people across the country and around the world, have difficulty talking about what happened.

“We talk about a lot of the good stuff, but every now and then, there would be a point of clarity where they couldn’t talk anymore,” Jacuk said. “A big part of what healing looks like for me, for our own communities, is to be able to speak the truth, to tell the story of those who came before us and were never able to.

“Because whenever we start to speak these truths, we not only find healing for ourselves and our community, not only for those who come after us, who don’t ever have to question who they are as a Native person, their importance, their identity, but also in telling the stories of people who went through a lot of this, through boarding schools, we’re able to find healing.”

Trulove described gathering in a talking circle as a path toward healing as an “ancestral gift.”

“The wisdom of sharing our struggles and pains through talking and listening has a long tradition in our ancestral past,” Trulove said. “… By attending a healing circle, exploring our history and talking with other survivors, confronting historical trauma, understanding the trauma, releasing our pain, and transcending the trauma, we can make sure that our descendants don’t inherit this terrible legacy.”

To learn more about the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, visit https://boardingschoolhealing.org/.

To learn more about the traditional healing circle, contact Karen Trulove at 907-335-7500.