Research shines light on boarding schools in Alaska

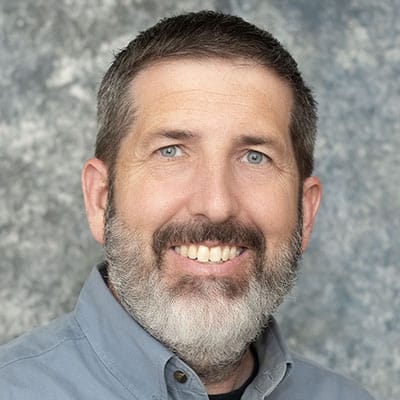

Benjamin Jacuk was surprised to be nominated for the 2022 Alaska Young Professional of the Year award, and even more surprised when he was announced as the winner.

But he is also grateful for the award, because it reminds him of the people who have influenced his life.

“I’m extremely grateful for getting it. My grandfather died last year, and it’s a reminder that he’s up there, still looking out for me,” Jacuk said.

Jacuk’s grandfather was Mackarius “Mack” Dolchok. His parents are John and Katrina (Dolchok) Jacuk.

“Whenever anyone needed help, he was always the first person to be there, no questions asked,” Jacuk said of his grandfather. Because of that, Jacuk added, many people called his grandfather “Uncle Mack” – even those who weren’t related.

“He was the one to teach me that’s what we do, not as only as human beings, but as Native people,” Jacuk said. “It’s all about helping, and building other people up.”

Jacuk, a Kenaitze Tribal Member, said his mother reinforced those values. Jacuk has gone on to earn master’s degrees in Theology and Divinity from Princeton Theological Seminary.

“(Helping others) is not only what we do, it’s who we are. And then you throw in the theology major, and there’s one thing in the Bible that’s very clear: go help those in need,” Jacuk said.

Jacuk’s main focus in his current work is research into boarding schools in Alaska. He has become an expert on the topic. His work has a very personal nature as his grandfather attended boarding schools growing up. Jacuk was also just the second Alaska Native or American Indian person to graduate from the Princeton seminary. A big part of the reason why, he learned, was that the seminary had “a massive hand” in establishing boarding schools in Alaska and across the country.

However, his theology studies provided him with access to resources he otherwise would not have known about. His studies also gave him a vocabulary for interpreting the research, and he has been able to pick up on nuances that might otherwise be missed.

In his research, Jacuk has been asking why and how churches and religious organizations had such a large role in boarding schools. He has also been asking two other important questions: “What did they intend to do with us as Native people, and what did they intend to do with the places we live?”

Jacuk has been working at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage as an Indigenous Researcher and Unguwat Program Manager for almost a year, but has been researching boarding schools for eight to 10 years.

In addition to his research, Jacuk also works to connect young adults, mostly in the Anchorage area, with their culture to prevent suicide and substance abuse.

“When people are able to live with their Native culture, it reduces suicide and increases wellness,” Jacuk said. “When we bring back culture, we give people ownership of their lives to live successfully with a Native lens in a modern world.”

Jacuk said he grew up on the Muscogee Creek reservation in Oklahoma but spent time in Alaska, especially during the summers, when he learned to fish from his grandfather and his uncle, Ron Dolchok Sr.

Jacuk has worked in many different areas for the betterment of Alaska Native people, including the United Nations Permanent Forum for Indigenous Issues. He is also co-chair of the Society for Pentecostal Studies Diversity Committee, which assists scholars from minority backgrounds with scholarships. He is an ordained minister and has led outreach events for at-need individuals throughout Anchorage.

Jacuk credits his grandfather for inspiring his work of helping others and shining a light on the past.

“It’s really him that I owe a lot of this to,” Jacuk said. “If I can bring healing to a place where there was hurt, it’s worth it. It’s about the past, and the future of those who come after us.