Tribe offers support services, but resources are limited amid strong demand

Surrounded by her belongings, Eunice Ruhl talks about her experience living as a squatter in an abandoned cabin near Kenai. The cabin has no electricity or running water. She has improvised a woodstove for heat and built an outhouse nearby.

Barehanded, breath visible, Eunice Ruhl knelt down, brushed snow off the log and propped it upright. With a grunt, she slung an ax over her shoulder and thrust it toward the ground.

The blade thumped into the wood, which crumbled into chunks the size of charcoal briquettes.

“Pretty rotten,” Ruhl said, catching her breath, “but it will do.”

To stay warm that night, it would have to do.

Ruhl is homeless and living on the central Kenai Peninsula, the tribe’s service area, a region known for its natural beauty and world-class outdoor recreation. But there are people living in vehicles, tents and dilapidated structures. And unlike larger cities, where homeless people and business professionals share downtown sidewalks each day, the issue is hidden in rural areas such as Kenai. The tribe offers support services, but resources are limited amid strong demand.

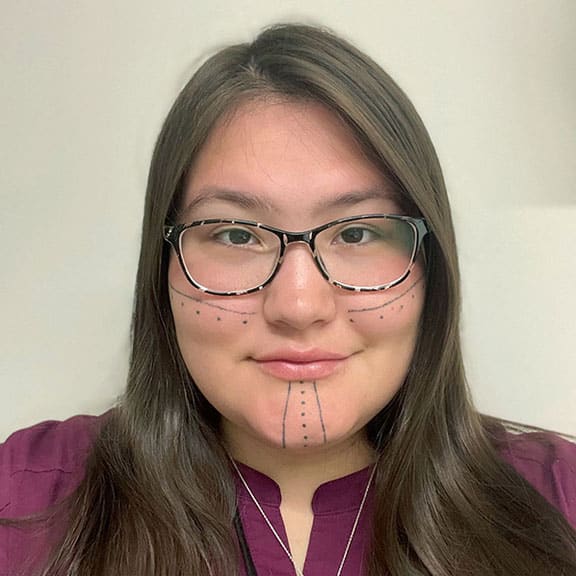

“The homeless aren’t in the streets sleeping. You’re not going to see them,” said December Shugak, who works in the tribe’s Na’ini Social Services Program. “They are in the woods, the trees, the beach, and that’s why so many people think we don’t have a homeless problem here. We do.”

Ruhl, 63, lives alone in an abandoned shack down a side road miles from town. The plot of land is cluttered with scrap metal, rusted vehicles and falling-down outbuildings. Coyotes howl at night, she says, and vehicles zoom up and down the nearby highway. Kota, a long-haired Chihuahua dog, is the only company she keeps.

Ruhl has been living in the rickety structure for about five months, working to make it habitable. She found a wood stove at the local dump and built a chimney from scrap metal to keep the place warm. Plastic windows, also from the dump, help with insulation. Blankets line the ceiling, rugs cover the floor, and there is a bed in a corner of the one-room structure. There is no doorknob on the front entrance, only a swinging door.

There have been no unwanted visitors, not yet, but Ruhl worries about drug use in the area.

Who might show up?

“I’m making it,” she said.

Ruhl, who is from the village of Ugashik in southwest Alaska, began struggling after her husband died in 2014. The couple had been living in the village, where he worked at a power plant and she ran trap lines and made arts and crafts.

But the cost of living was high, and it was too expensive to stay on her own.

So Ruhl, who identified herself as Eskimo and Aleut, moved to the Kenai area to be closer to family.

She assumed a seasonal lease on an apartment, but the situation fell through and she couldn’t find another place to live. She came to the tribe’s Na’ini Social Services Program seeking assistance.

The tribe gave her a two-man tent and a gas stove. Then Ruhl discovered the abandoned property. She decided it was her best option.

“I just couldn’t make it anymore,” she said.

Because the property is located miles outside town, and Ruhl does not own a vehicle or possess a driver’s license, transportation is a problem. A roundtrip cab fare costs about $30.

Social services professionals agree that transportation is a barrier for those in need. Public transportation is limited.

The Central Area Rural Transit System offers low-cost rides, but only on weekdays. A new bus line runs from Ninilchik to Soldotna to Kenai, but only three days a week, and it does not reach the outlying communities of Sterling and Nikiski. The tribe offers transportation, but riders must meet eligibility requirements.

That the Kenai Peninsula is about the size of West Virginia only compounds the issue.

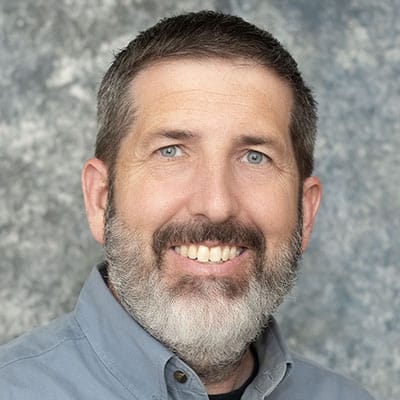

“Transportation here is probably our No. 1 issue,” said Elizabeth Kleweno, a social services specialist with the tribe. “It is the biggest issue and the costliest.”

Eunice Ruhl, 63, swings a splitting maul to make firewood for her woodstove. Squatting on the land, she uses the cabin behind her for shelter and the shed, at left, stores trash previous users left on the property.

Ruhl, who receives about $1,000 a month from her husband’s pension, believes she could get a job if she had reliable transportation. She enjoys manual labor and says she has applied for positions stocking shelves.

But without a steady way to reach town, it’s difficult to get hired.

“I want to work,” she said. “I like to work.”

The pension money, Ruhl says, is not enough to cover necessities in addition to rent. Medical costs, transportation, food and incidentals swallow her budget.

For people on a fixed income, or with no income at all, it can be difficult to obtain affordable housing.

Although the tribe and other local agencies offer subsidized housing, which reduces the cost of rent on a sliding scale based on a person’s income, local options are limited. The application process also can be a barrier for those with criminal backgrounds.

One of 32 units in the tribe’s Toyon Villa Apartments in Old Town Kenai is designated for transitional housing, offering free rent. Sonja Barbaza, the tribe’s housing representative, said there is about a 10-person waitlist for the unit. Four other units in the complex are subsidized by the tribe. Barbaza said the waitlist for those units is about 20.

The tribe also works closely with the Alaska Housing Finance Corporation to offer subsidized housing. Barbaza encourages those who come to her to apply for the program. If accepted, they can live in the tribe’s apartments or units managed by other landlords at subsidized rates.

But a criminal background check is part of the application, which leads to denials. Some people, Barbaza said, don’t even bother applying.

It’s a challenging dynamic.

“Homelessness is what causes the violent crimes and all those things in the first place because they aren’t having their basic needs met,” Barbaza said.

It is not known how many people are homeless in the area.

Cheryl Carattini, another social services specialist with the tribe, said local nonprofit Love Inc. served more than 300 homeless people in 2017. Project Homeless Connect, an annual event where local organizations offer support and resources to those in need, has grown since its inception six years ago. And about half the people served through the tribe’s General Assistance Program, which provides essential needs, are homeless.

“It’s talked about but I don’t think it’s actually known how bad it is here, how serious it is here,” Carattini said.

Shelters in the area provide some relief.

The Friendship Mission, a faith-based shelter in Kenai, serves men. The Freedom House in Soldotna, also faith-based, serves women. Then there is the LeeShore Center in Kenai, housing women who are victims of domestic violence and sexual assault. There also is Indigo Recovery Housing in Kenai, providing transitional housing.

Those places cover some of the need, but not all of it, said social services specialist Elizabeth Kleweno.

Another challenge is paperwork.

Many of the tribe’s services are funded by grants that require demographic and other information about program recipients. If a recipient doesn’t have the required documentation, the process is slowed and it’s difficult for the tribe to help.

Eunice Ruhl’s living conditions are better than those of some homeless people. “I’m making it,” she said.

One man, who goes by the name Two Wolf, lives alone in a tent in Kenai. The tribe has helped him with everything from food to emergency lodging to warm clothing.

But it took about a month for the tribe to complete a required income verification, said Roberta Turner, the tribe’s social services program administrator. A challenge the tribe faces is getting program recipients to follow through when information is needed during the application process.

Delays are frustrating for everyone involved.

“To the person living on the street, to them, time is of the essence,” Williams said. “They want to get things going now. Like food stamps. I need food stamps. I’m hungry, I haven’t eaten. Then I have to wait. Wait a minute, I could be dead by then.”

Participants in this story, both the homeless and those who serve them, had varying ideas for solutions to the issue.

More shelters. More affordable housing. More transportation. More funding. More education. More behavioral health support. More accountability. More community awareness.

“We try,” said Kleweno, one of the social services specialists. “We try to help in whatever way possible.”